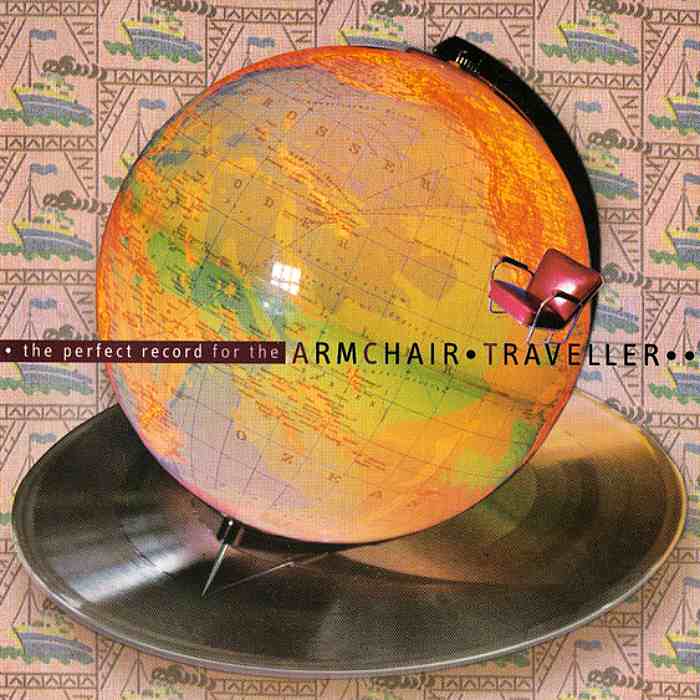

Nowadays, the music of foreign lands and peoples arrives postpaid from a plug in the wall: World Music! World Music? Under this handy label, a strategic marketing battle cry against the tired body of pop and classical music of Euroland and the North American continent, sickly-sweet pablums in sundry flavors are concocted from all kinds of exotic ingredients that are combined, congealed in a sticky synthetic digital sauce, decorated on top with colorful bits of samples – and served ready-to-hear. Why understand, when you can just enjoy; why differentiate more precisely where the musical properties come from? Why learn more about the original music – its cultural contexts, its peoples, places and rites – when it is enough merely to cleverly arrange the exotic sounds in a way that provides the largest screen for projections of wanderlust, and so satisfies our longing for ostensibly authentic foreign elements. But don’t let them get too close, if you please!

ArmChair Traveller plays it inside out, twists the facts, and so perhaps finally brings forth the real, authentic, ethnic music of our time. It is real, because everything about it is unreal; it is authentic, since it has just been totally invented. But it sounds archaic because it has been created by musicians who have developed specific playing techniques, mostly on their own, for handmade instruments built from everyday materials and for conventional instruments they have specially prepared. It is ethnic because chance providentially brought these musicians together at the same time in a big city like Berlin – metropolitan centers have become homelands for quasi-ethnic groups. Armchair Traveller’s music always sounds somewhat «as if», it denies its ancestry by not denying it; it plays with exotic atmospheres, but always conditioned by multiple refractions, like billiard balls caroming off the cushions. The individual pieces, imaginally located on various meridians of the globe, sound like tribal music that somehow is simultaneously experimental and (post)industrial. Much of it sounds electronic, but everything is acoustic. Sebastian Hilken’s cello, bristling with paper clips, sounds like a Mbira, the African thumb-piano. Werner Durand auditorially transforms his PVC tubes, with their plastic bag membranes and saxophone mouthpieces, into a drill. Hella von Ploetz rubs the glass rods of her glass harp with water, or bows the metal sheet that serves as its resonance board, eliciting sounds that evoke the mirage-like foghorn of an ocean steamer deep in the desert, or the trumpeting of elephants. Silvia Ocougne plays every possible variant of guitar and modified guitar – tiny children’s guitars, samba guitars, and a guitar strung with crossed strings that sounds like no guitar one has ever heard before. An Indian Tambura is played like a Brazilian Berimbao; the embouchures used for the Arabic and Iranian Ney are applied to PVC tubes. Flower pots and aluminum pizza pans also acquire a voice. The instruments start to sound so different that you can no longer tell them apart. And so, Laos and Sao Paolo, Patagonia and Portsmouth, Ghana and Gera meet musically in the homey family room, which projects the exotic fantasies back upon itself. Travellers in their armchairs discover -at once alienated and fascinated – the foreignness in themselves. Hindustry!